Czene Márta: Fade-In

5 November 2014 – 5 December 2014Átmenet/Fade-In, the exhibition at Inda Gallery, presents the latest works of Márta Czene. This time, beside her paintings, the public is also introduced to her recent drawings, photos and videos. For the exhibition Inda Gallery, the National Cultural Fund of Hungary (NKA) and the King Saint Stephen Museum of Székesfehérvár are also publishing a 120-page catalogue covering her entire work from 2010 to 2014. This publication, edited by Brigitta Muladi, also contains two essays by Sándor Hornyik and Dávid Fehér. The following text is an abridged version of Sándor Hornyik’s essay, Vertigo.

„If we state that the object of desire and analysis in a woman's painting is none other than the woman herself, we haven't said much. But if we also add that that certain woman not only internalizes but also deconstructs the fetishized, model-like female form of the late capitalist society, we get closer to the requirements of scientific hypothesis. In fact, if we also add that in Márta Czene's case this process of interpretation is not only intentional and conscious, but is also based on repetition and the narrativization of paradox, we immediately find ourselves in one of the legitimate fields of contemporary, hypermediatized painting.

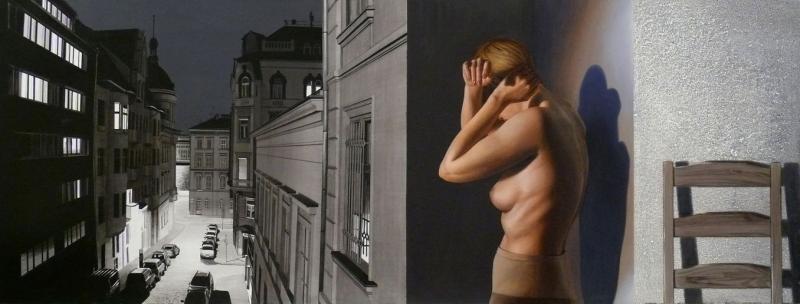

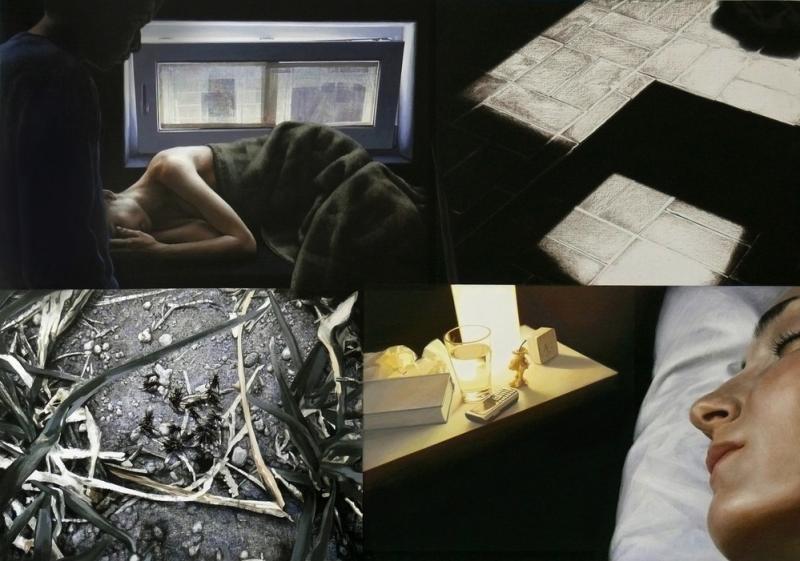

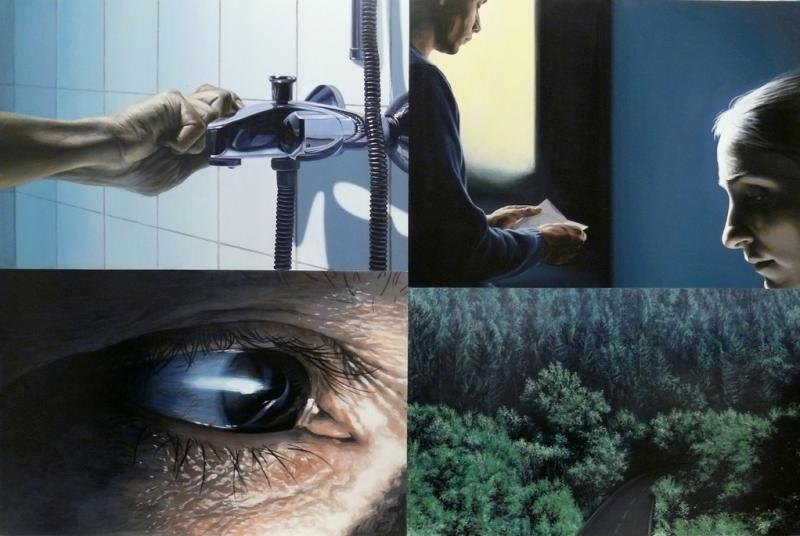

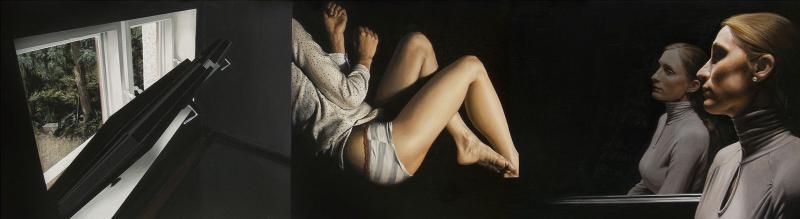

Márta Czene, by the way, feels at home in art history, film-making and psychology, in fact, the creative joining of the three has become one of the major driving force of her painting. We can see this in two of her projects: My movies (Saját filmek) is a scenic “re-shooting” of the films of Dario Argento and Roman Polanski, and in Focus (Fókusz), she examined the pictorial and poetic relations of subjective and objective reality, as well as painting and photography, with the use of a psychoanalytic method that is based on reminiscence. Timeline (2011) doesn't exactly look like a storyboard, although the emergent “film” evokes the atmosphere of a haunting montage, rather than the illusion of a coherent narrative. This cinematic, storyboard and collage attribute is more and more de-emphasized in her recent paintings; the vacuum between the pictures, that is, the “white frame” disappears, and the frames are merged into each other, and in accordance with this, the particular film references and quotations also give way to a kind of free association game. The techniques of remake and recycling are gradually replaced by an auteur; a self-aware, yet mysterious author is in the centre, who seems to paint the same woman time and again…

Speaking of epistemology after the analysis of sujet and pictorial visual, we should point out that Czene, with her reflections and pervasions, would prefer Louis Althusser and the world of ideology to Lewis Carroll and fairy tales. Inspired by Lacan's mirror stage, in the centre of Althusser's theory there is the method of the subject becoming a part of the ideological construct of reality, as the viewers find themselves in the pictures and concepts that society and the symbolic order provide them with. In fact, Althusser uses the enchanted castles of amusement parks, specifically, the metaphor of the mirror hall, where the endless row of mirrors makes us recognize ourselves as objects and subjects at the same time. Czene's Mirror (Tükör, 2013) perfectly fits into this ideological interpretation, especially if we include Tarkovsky's film (The Mirror, 1974) as well, that thematizes the role of remembrance in the creation of self and self-image. From this point of view, Czene's “mirror” seems to mean that the strong, confident and independent woman, that is, the female hero, lit dramatically from underneath doesn't need mirrors, in fact, she doesn't even acknowledge them, because she can autonomically build from herself.

Reflection gains a completely different role in a painting from 2013, Nature 1 (Természet 1), with another beautiful, blond woman, whose image is reflected in a vehicle's large window. Following the reflected woman, the other two “frames” of the triptych create an ominous atmosphere. In the central picture, we can see an supposedly suffering female body in embrionic position, and in the third one, we can see nature itself through a couple of small windows. Nature 1 has a twin-painting as well, thus, the two works could be two related triptychs, or the two predellas of an altar, or even two times three film frames. In Nature 2 (Természet 2, 2014) the motif of death gains a particularly strong visual emphasis, because an amazingly lifelike, painted hand is associated to the two triptych's depictions of nature, with insects crawling on it, that is an unequivocal association to the dead body. Together, Nature 1 and 2 leave the analytic and hermeneutic context of earlier works, and evoke the iconography of depression and death much more strongly, while also containing associations that transgress it.

The key to further iconologic interpretation could be a film reference again, none other than Lars von Trier's Antichrist (2009), where similarly to the Alien-franchise there is a strong woman who cannot control her strength and anger, mostly because she cannot find her way out of the maze of ideologies. …

While Trier examines the modern, ideological hall of mirrors and the tragedy of women's victimization, the analytic nature of Czene's pictures and the poetic nature of montage also offers a kind of escape route from the labyrinth of images and ideologies. …

Czene's threatening narratives and suspenseful images are also ominous, but on a meta-level: during editing and directing, her works are impregnated with a kind of personal aspect and humanism. The topic of her paintings is not primarily the barren, psychoanalytical space of the gaze, but the female subject, that gains a personal aspect in the space of representation, because there are living people, real persons behind her characters. It also indicates that Czene uses her paintings as a kind of lacanian écran, that is a metaphorical screen or realistic canvas, where she attempts to project her own films, the images of her personal, optical subconscious, that embarrassingly interfere with the visual cultures of the past hundreds of years from the painting of quattrocento, through the Dutch still-life and the imagery of the surrealists to the present, to David Fincher's and Lars von Trier's films. This huge and inward perspective may allow us to interpret Czene's écrans from Lacan's point of view to tame the gaze (dompte-regard). Lacan defined the gaze independently of social gender roles, and according to him, it originates from the symbolic order that marks the possible positions of the subject through language. But this is so typical of Heidegger and Sartre, it implies such a hopeless and exposition to a world on anxiety that can only be internalized if the subject can accept and understand her exposed situation. It doesn't mean that vertigo will disappear in a flash; dizziness and anxiety cannot really be cured, but it can be treated and controlled. A possible, in fact, preferred instrument of this is the kind of art that can project and depict the complexity of human relationships, boundaries and reflections, and the haunting, enchanted castle we live in.”

Transl. by Zsanett Horváth and András Gerevich

BACK