Best Before End

14 April 2010 – 28 May 2010When is the work finished? When the artist „finishes” it, or when it is exhibited? Can we exhibit a sketch, is it interesting enough to be exhibited, will it change its role and seem finished? There is a saying about drawing: you can stop drawing, but cannot finish it. Does it apply to the pieces of art in general? The nature of the works can be different, some of them are prepared according to a planned method, and resemble a precisely finished industrial design object, but others may seem rough, or need patina prematurely.

The medium of a two-dimensional work is a matter of decision, there are no rules, you can paint, draw, apply or project photos or motion pictures on anything, and even the multi-dimensional objects have an infinite possibilites of mouldable materials. In the Renaissance it would have been unimaginable to consider a work of art Leonardo's barely sketched St. Anne (according to the standard of that time), or Gustav Moreau's the recently exhibited sketches in the Museum of Fine Arts, all of them are presented now as equal to the finished pieces of art, and their invisibly fined surfaces and lines, that are covered on other paintings, enchant everyone. The presentation of architectural sketches and plans is a routine, and the quick drafts often tell more about the architect's spatial thinking, and the final look of the building than the finished blueprints.

In the case of fine arts, it is different: the artist can decide himself in which phase he wants to exhibit the work. This time, in our exhibition, what we can see are not necessarily the works intended for presentation. We can peer into the artist's imaginary, magical studio by catching a glimpse of the work in a stage when it is not qualified as a finished piece. It depends on the artists' practice whether they keep the sketches and plans or destroy them, consider them separate works, and they get into collections and exhibitions with or without the finsihed work.

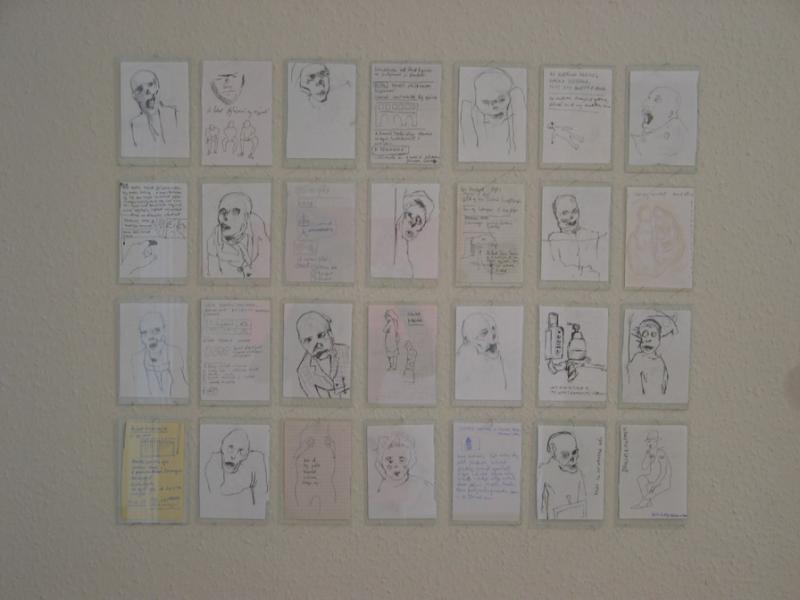

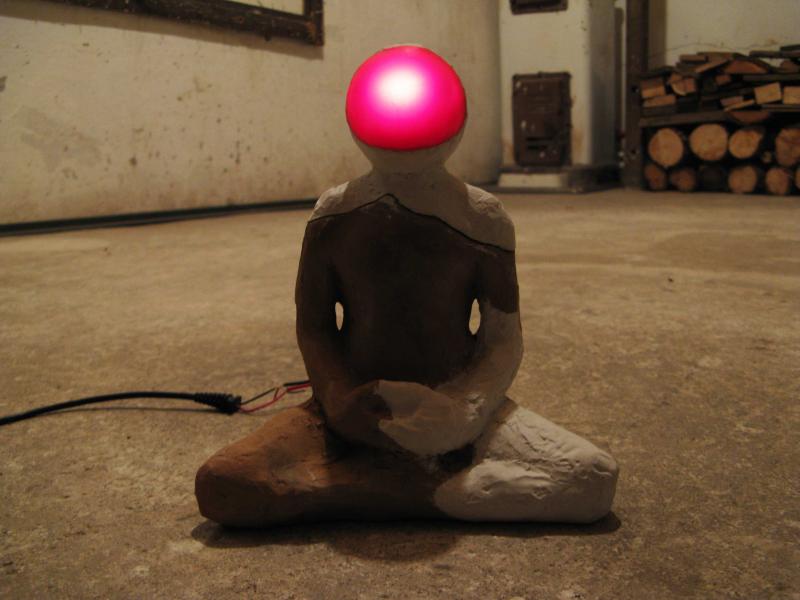

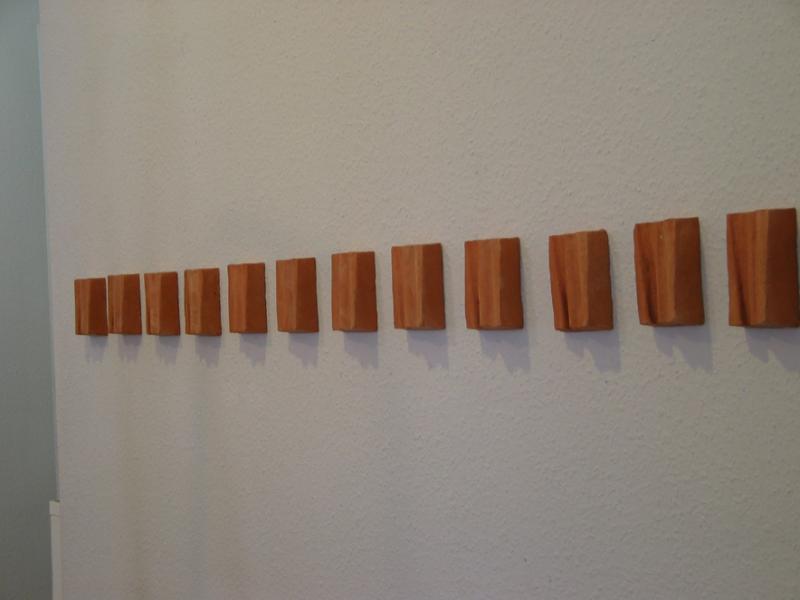

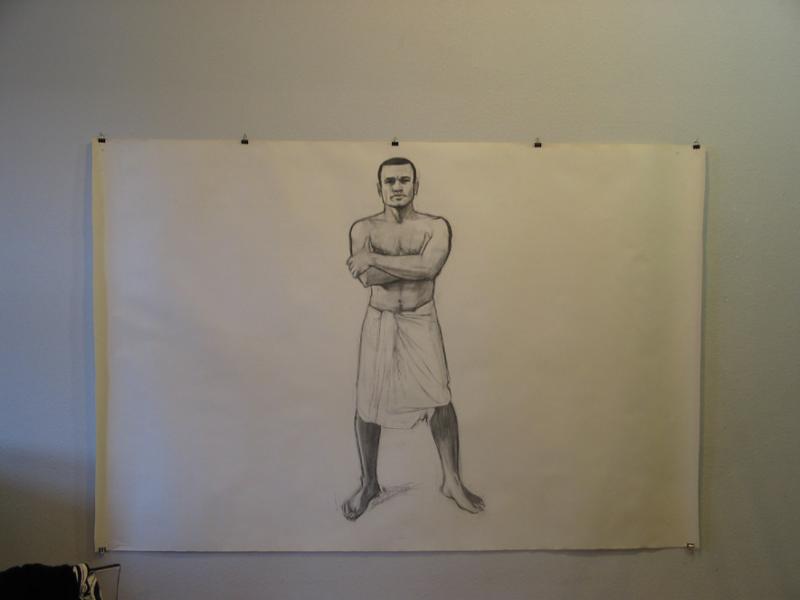

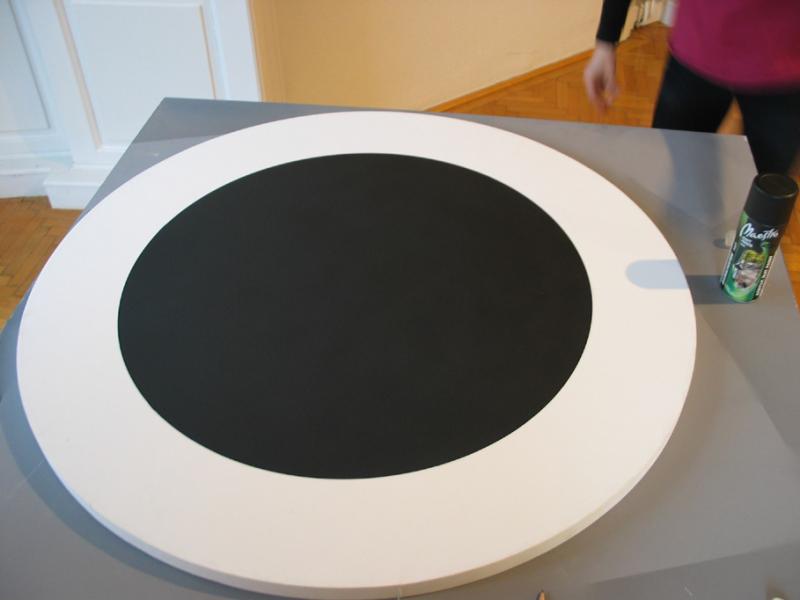

AKA (András A. Király) re-shapes bare walls, abandoned buildings and public urban spaced on his drawings. He works out a complete permission plan and creates the work on the spot. His exhibited sketches present the re-painting of a waterworks engine-house and a supporting wall, both are in progress during the exhibition. Márta Czene is famous for her accurate, precise, dry-paint figural paintings, but we have not yet seen the preceding re-painted photos and sweeping sketches. This time she arranges them in an exciting installation. Zsolt Ferenczy's environment gives us insight to the current condition of the forever-changing studio-corner. We can see the first versions of a few works we already know, like Tamás Ilauszky's the small drafts, that were drawn for his paintings of unexpected associations and linguistic inventiveness; or György Jovián's sketches of the chosen reality-detail photos that he magnifies by a tone-block. Diana Keller exhibits the work photos of her latest videos, and Péter Somody's colour sketches are also connected to the previously seen series. Ádám Szabó's installations and sculptures are preceded by drawings, and this time we can see the model of an older work. Henrik Martin, living in seclusion, has been working on the projekt Space Buddha, and now he exhibits its small requisites. Zsófia Szemző presents a few pieces of the drawings of the first phase of her new work. We can see a selection of the photos preceding blow-up and the drawings of Péter Puklus. The sketches of Emese Benczúr show us the plans of an exhibition without artworks. It is a question of determination whether Ágnes Szépfalvi's drawings of models, Ábel Szabó's photos, and Krisztián Sándor's drawings are considered finished or sketchy. Until now, we have not known that Lajos Csontó also draws, and now we will learn what and how. Tamás Kopasz always finishes his works in one breath, all of them are quick improvisations of a long, preceding concentration, and contain every phase of creative work. Endre Koronczi presents a complex projekt still in the research phase, which ironically elaborates the quite absurd form of gender roles under the flag of „panem et circenses”. The photo sequence, that is considered plain air practice, was made in the Tuning Show arranged for men, where women pose with four-wheelers on sale like playboy bunnies, and men of all ages join them gladly. Kamen Stoyanov flips classical art in his own sarcastic manner: his work is finished when the picture is hung on the wall, as the artist says. His action begins with the adjustment of a leaning picture, titled The crisis of balance, in the contemporary museum of Montenegro. It ends in Inda Gallery, video and text is added to the record of the action: the hanging of a round canvas titled The picture that cannot be leaning.

Brigitta Muladi art historian

BACK