Czene Márta: Focus

16 December 2010 – 28 January 2011In line with the exhibition, at the opening ceremony we will introduce Teaser, a book of Márta Czene, which summarizes her works of the first ten years monographically, based on her exhibition in the Vaszary Gallery in Kaposvár. The book was published by the Vaszary Gallery.

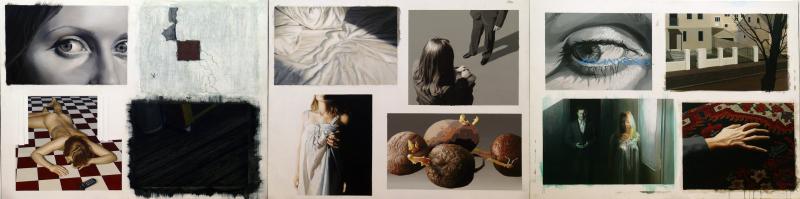

In 2000, when creating the montage-imagery of Snatch, Guy Ritchie may not have thought about the Russian avantgarde film makers or the American David W. Griffith, who were among the first to use montage. Maybe he did. But the audience don't necessarily have to go the cinema to see it, because the commercial, digestible television thrillers and action films often use divided frames on which the obdurately approaching wicked and his ignorant victim can be seen at the same time. No matter how simple these computer effects might seem to be, these panels draw upon such traditions of European film making that have nearly a hundred-year-old preliminaries. Both in the fields of fine art and cinematic art, several innovations were made during the Soviet avantgarde of the 1920s and 1930s, for instance Dziga Vertov's „cine eye” (kinoglaz), according to which the camera can seize the world more perfectly than the human eyes. Vertov's silent film of imagery, the Man with a Movie Camera (1929) was restored and scored by the Cinematic Orchestra in 2002. In this work, Vertov documented his environment in a sensitive way; he painted an imagery by the hand-held camera popularized by Rodchenko, in which aerial perspective, clean spaces, close-ups, and decomposed details rhythmically change one another. The additional work after the fast motion of the camera, the editing and mounting were just as important as the shooting itself. The superposition of slow-motion pictures and stills was meant to imitate realistic perception. According to Eisenstein, montage is the tool of the clash of representations and the creation of tension and dramatic power. The montage, the different visual angles, luminous sources, the shots (close-ups and wide-shots), sections, and changes of scale are thought-provoking.

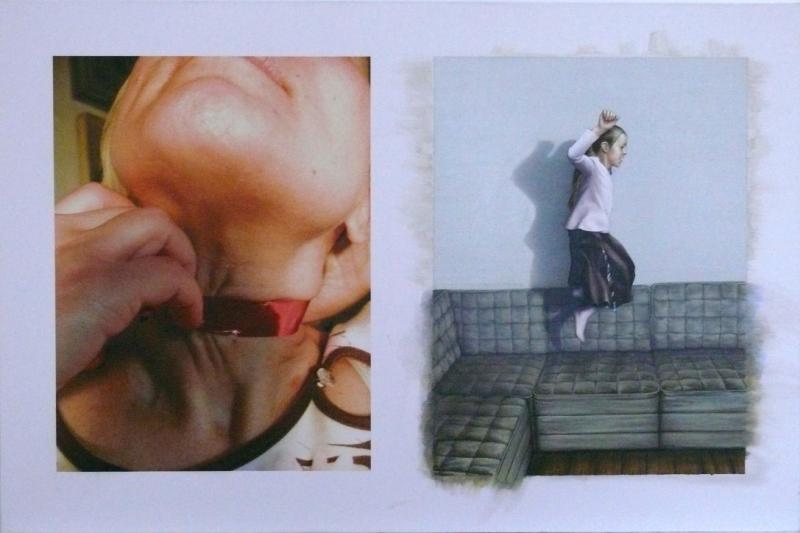

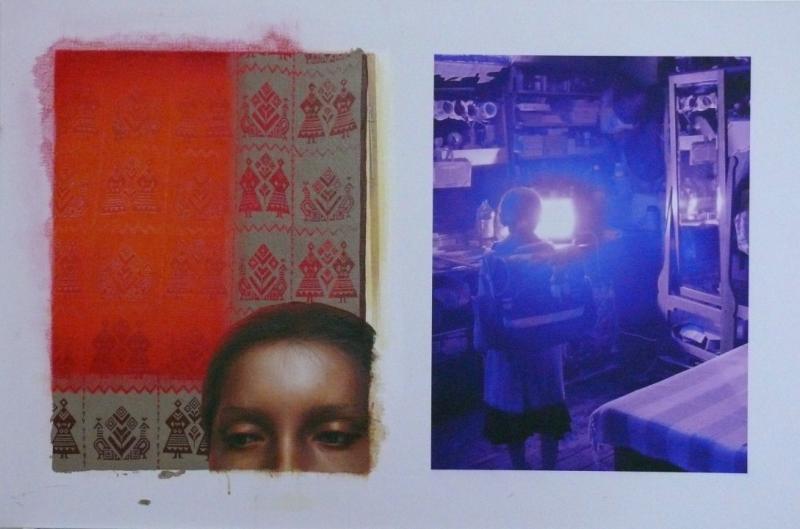

The Focus sequence, the central part of the exhibition in the INDA Gallery, also uses the montage technique. I quote from Márta Czene: “On one side of the pictures we can see a printed photo, and on the other, a painting. (...) My friend recalled the memories of my childhood and other experiences. While reliving these experiences, I often remembered another relevant scene. I painted the pairs of pictures based on these experiences. They are partly autobiographical, and partly the mixture of imagined elements; the contrast of photo and painting also refers to the fact that what I paint refers to objective reality only to a certain extent. I depicted stories and alternative realities through which I could reflect upon my life, my personality and its possible developments. At the same time I was interested in the differences of the genres photography and painting, as objective and subjective, and the juxtaposition of a photo and a seemingly photo-like, but rather sight-like painting following Renaissance traditions.”

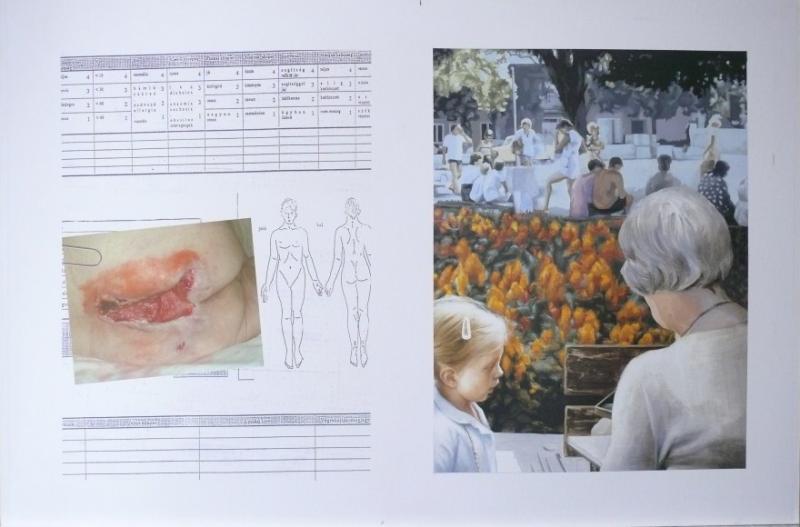

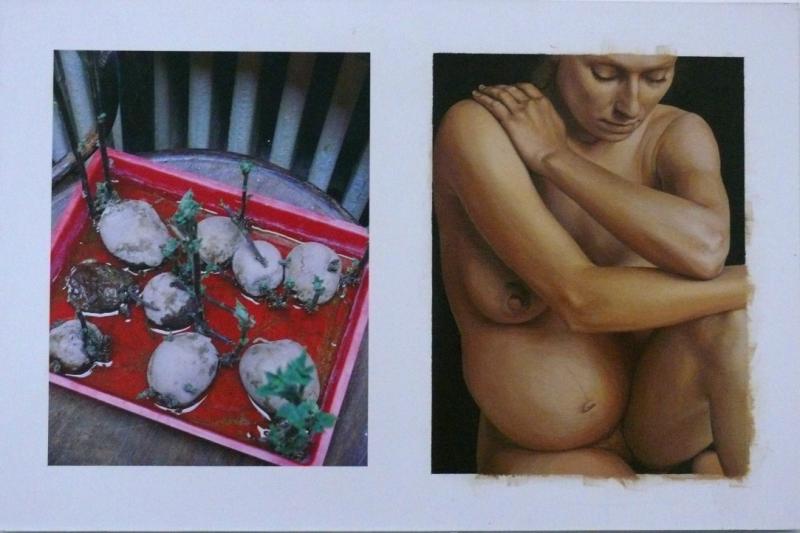

Márta Czene often expresses her views on feminity through the naked body, into which she condenses her self-image and expresses her secret thoughts indirectly. She doesn't use her own body in order to create the form, instead she borrows her friends' bodies, as if inspired by the ancient notion that replaces reality with an ideal object between reality and imagination, which in this case is realized in the ratio and aesthetics of a chosen, existing body. And this body is not a symbol, not an allegory, not a nude, not an ideal image, and not even a reflection, but a real body, whose model was a young woman of the same age and sensitivity than the artist. With this train of thought connects the natural and shocking picture that may be difficult to interpret, portraying the horror of the bedridden grandmother's long illness and death and her person reconstructed from memories, which sheds light on the previous statement, that the representation of naked bodies refers to the point where reality enters the imagination. On the left side of the picture we can see a document about the grandmother's bed sore, reserved words about an open wound, and under it there is a photo of the real condition, which is actually raw meat. On the right side of the picture there is a family portrait of the grandmother sitting with her back to the five-year-old, perhaps drawing artist, and the entire milieu appears as a stereotype of social-realist happiness, in sharp contrast with the brutal reality on the opposite side. By placing an excerpt from a story of a family and the diagnostic results next to each other, the changed relationship of art and reality appears, and the brutality of death is opposed to sentimental realism and the symbolic vanitas pictures of art history; eras and ideas clash. The association and extension of the contrast of the pair of paintings confirms and is connected with Eisenstein's opinion, that the simultaneous 1 image + 1 image = 3 images. We can find several examples for the savage efforts of contemporary photography and cinematic art to expose reality; this picture reminds me of Kader Attia's collection which is selected from the archive of injured soldiers' portraits: photos of distorted faces with undisguised, terrifying fractures caused by bullets and splinters. But there is also an interesting period of Cindy Sherman, when she imitates injuries and wounds on her set photos.

Our inner images are part of the mental machinery that controls fear, feeds on psychic injuries, transforms them into images and lessens their effect. According to Dietmar Kamper this inner image set protects us from too much reality, and materializes experience. (Cf. Focus sequence)

Márta Czene mixes realistic perception and the pictures of moments with these inner images whose projected forms draw upon films. Her efforts lead her to create total realism, vivid pictures either in photo, video or in interactive games, that are the closest to the eclectic, linked method of our perception of everyday reality, and its final interpretation is given by the audience.

Brigitta Muladi art historian, curator of the exhibition

BACK