Jovián György: Brave New World – Demolitio II

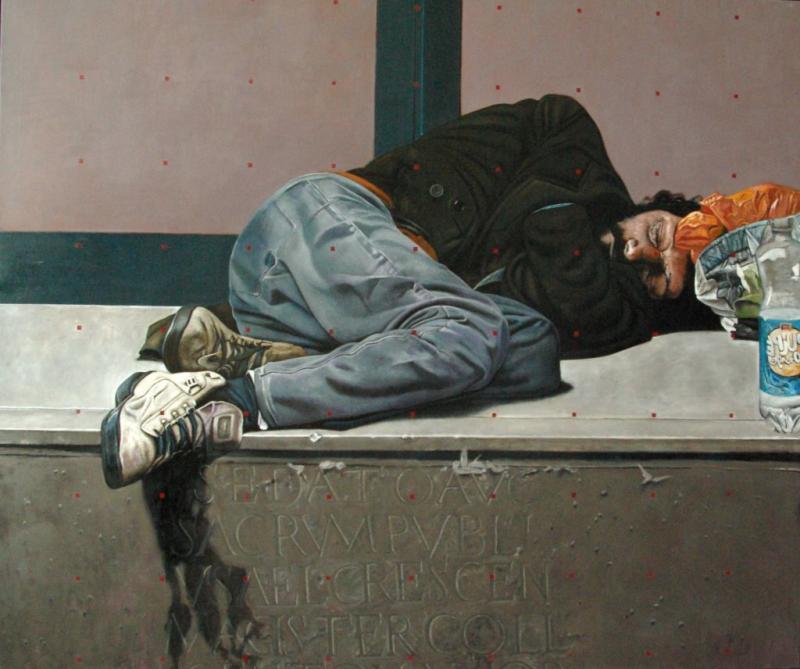

22 September 2010 – 15 October 2010Psychologists use every effort to save us from anxiety by confronting us with our fears, searching for the origin of neurotic experiences, and neutralizing them by bringing them to our consciousness. The painter's hypersensitive sensors are exposed to overload, he's aware of the causes of anxiety, he doesn't need to look for them because they are visible - in this case they are lying in the streets.

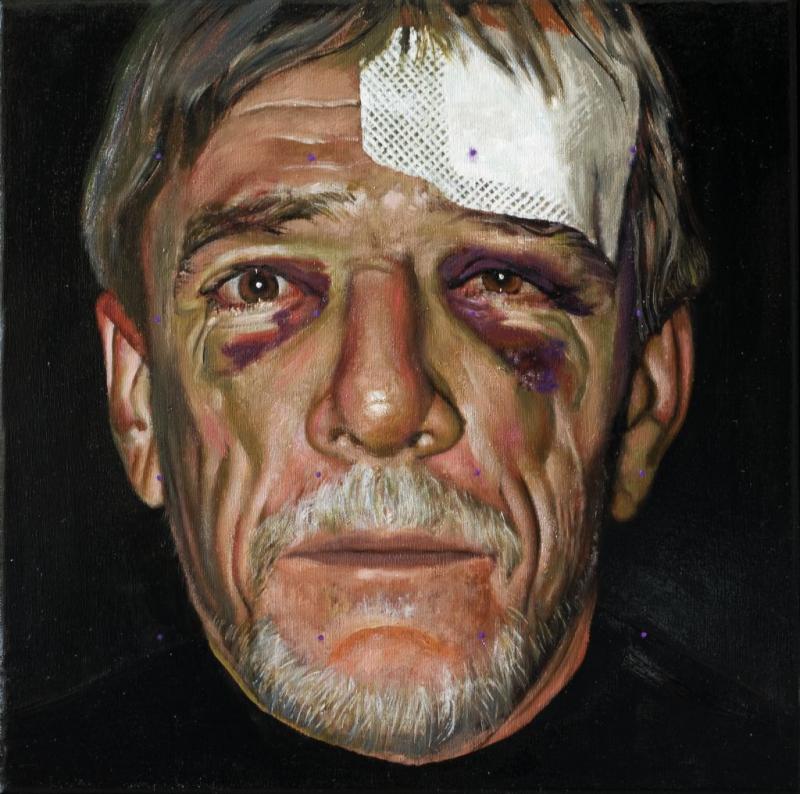

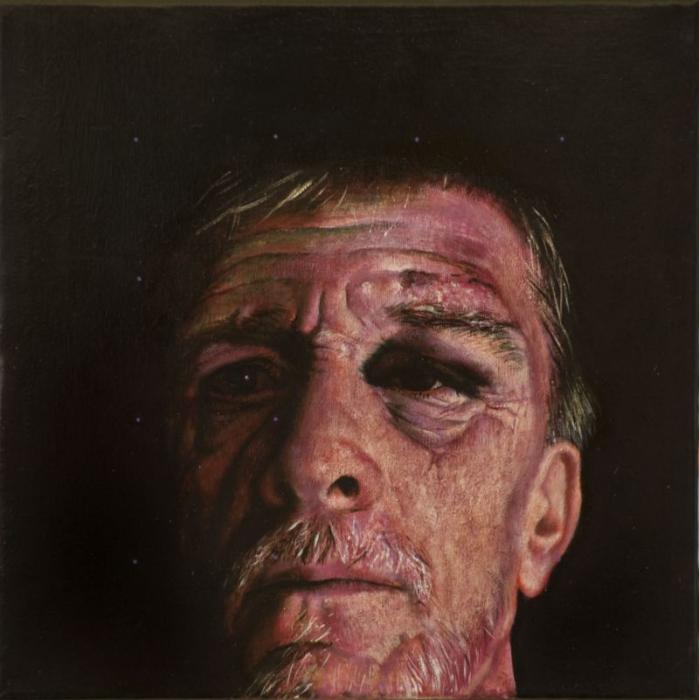

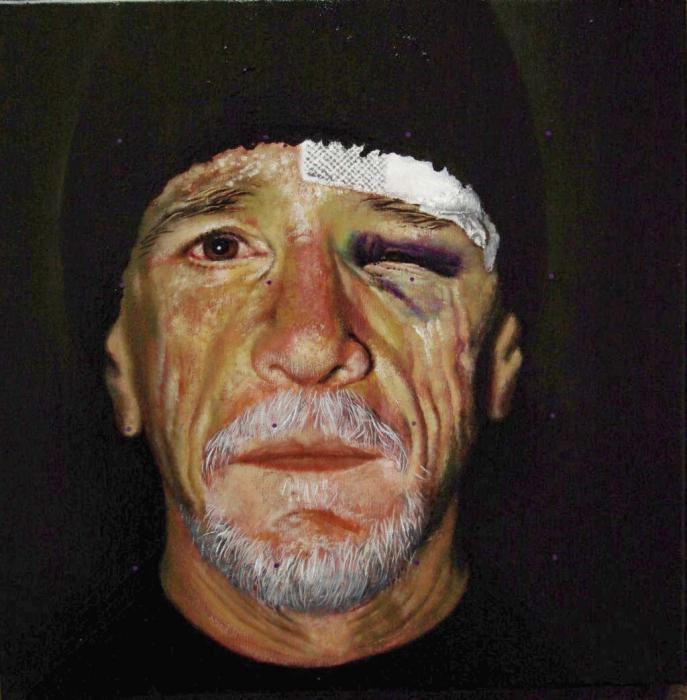

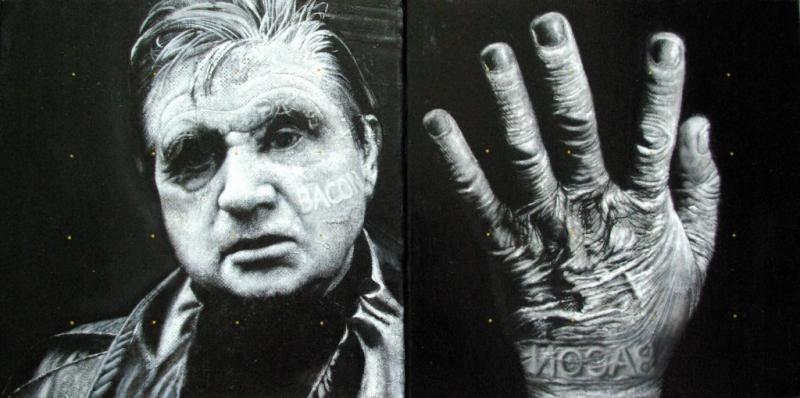

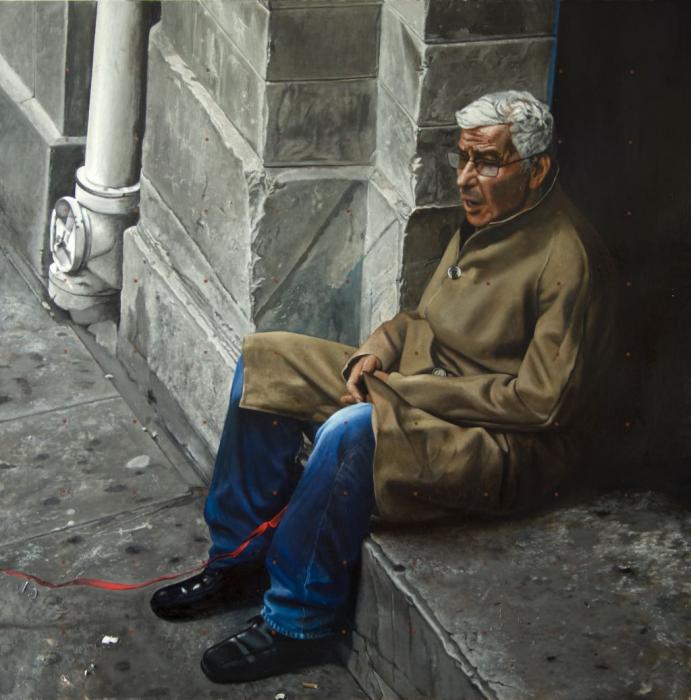

For years now, György Jovián has been working on a painting series representing the waste of humans, the live or lifeless „useless” by-products enlarged and frozen. The objects of the depictions produce a multiple dramatic effect, and rouse sympathy as well as an intimate closeness in the audience, and the cold objectivity, the alienation, perhaps even scepticism of the painting technique don't weaken it, on the contrary, they intensify this effect. The shocking effect and the psychological profundity are most palpable in the case of the self-portraits of real situations, Study of an Accident (Tanulmány egy balesethez), and the pictures portraying homeless people. We often understand what the picture represents only because of a tiny telltale sign. For instance, we might think that the Man with Leash (Férfi pórázzal) is merely the portrait of a middle-class man, but the stained coat and his perturbed expression make us unsure; the dramatic, raw architectural background emits a strange, sultry atmosphere.

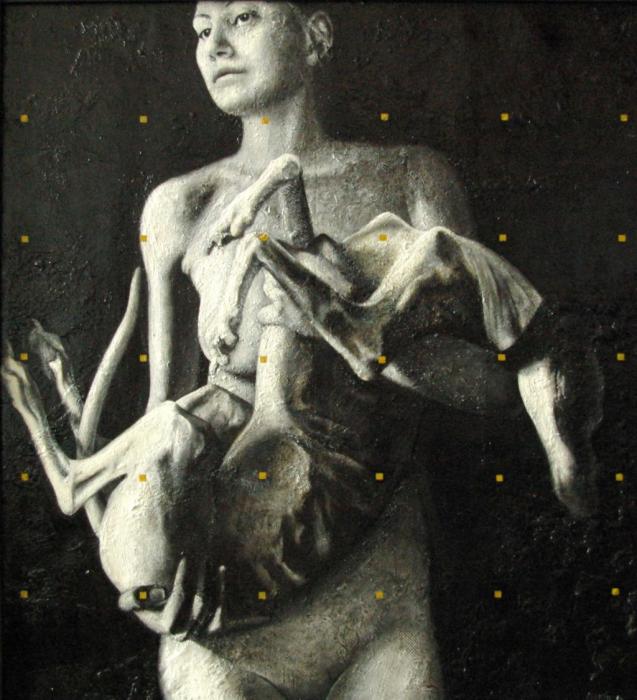

The paintings show reality to us in a realistic, unrelenting way, yet every work is surrounded by mystery. The Flame (Láng) is the most enigmatic one, the (last?) portrait of a half-naked man sitting on a sofa, insinuating but not confirming a suicide, as well as the Girl with Dead Dog (Lány halott kutyával), painted in honour of Lucien Freud. It is not because of its external features that Lucien Freud's prolific painting in Baroque style got into the reduced form system defined by the great predecessors: Caravaggio, Vélazquez, and the contemporary Anselm Kiefer. Freud also depicts the human defencelessness and frailty in an immensely sensual, crucial manner; his most conspicuous touchstone besides the opulently painted bodies is the stunning intensity and vastitude of the postimpressionist colouration. Jovián, on the other hand, works with an ascetically gaunt, photorealistic form system and reduced colour palette; in addition to the greys, browns and whites he uses a minimal amount of cold blue and Tuscan red, but usually only on the colourful, punctiform signs in the intersections of the raster of enlargement.

The most interesting circumstance in György Jovián's exhibition is the return of human representation, which had already been repeated several times during his career, but it has changed significantly since the Aquarius. The body of the pseudo-mythological figure wrapped in mysterious fabric from the eighties formally resembles the heaps of building rubble and debris of the first decade of 2000. Its sharp photographic appearance leads to the relentless realism of contemporary human portrayal, which, with a twist, calls the audience to participate while it deals with the same topic: the dramatic profundity of human existence.

Brigitta Muladi art historian

BACK